Musician Jahan Yousaf on Giving Back to Pakistan

APF Leadership Council member Zehra Ansari recently sat down with Jahan Yousaf of Krewella, the electronic dance music duo of Jahan and her sister Yasmine Yousaf.

Jahan spoke to APF about her musical journey, her relationship to her Pakistani heritage, and how she gives back to Pakistan.

Jahan established the non-profit organization Nagar women’s Health House in February 2021 in the remote northern Pakistani village of Nagar to provide free access to healthcare services.

Krewella’s latest album “The Body Never Lies” will be released March 4, 2022.

Zehra Ansari: Tell us about yourself and how you became a musician.

Jahan Yousaf: I grew up in a very multicultural and fusion-oriented household in the Chicago suburbs with my my two sisters Aisha and Yasmine. Our mother comes from an American-German-Lithuanian background and our father was born in Pakistan. Our mother truly took the lead in learning and preserving Muslim traditions and Pakistani customs at home, whether it was the food we ate, cooking breakfast at dawn for us during Ramadan, or sewing the outfits we wore going to Islamic school and desi gatherings.

In 2008, when Yasmine and I were full-time students with jobs, we started dabbling in music as a hobby. Since we were consumed with jobs and school, our experimentation with music as teenagers was usually reserved for time off on weekends. It was a playful, liberating outlet for us that provided catharsis amidst mundane, sheltered, suburban life.

Early on, we were inspired by our discoveries of electronic bands like The Faint, Cut Copy, and Daft Punk. Electronic music felt incredibly futuristic and cutting edge at that time. Around 2009, we began exploring the pulses of electronic music by getting involved in the clubbing scene in Chicago, which helped form our emotional bonds to dance music. We’ve been creating music and touring the world ever since, and falling more in love with what we do as time passes.

ZA: What were your early musical inspirations?

JY: Growing up in the Yousaf household, we had access to such a diverse range of music collected by both of our parents. The cabinet with tapes and cds in our living room was like a treasure chest, where we would spend hours discovering an endless amount of albums. We'd go from singing along with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan (whose Urdu and Punjabi words we didn't understand) to bumping Technotronic and singing harmonies over songs by The Beatles. We were also drawn to the soaring melodies of Abba, captivating lyrics of Alanis Morisette, and angst of Sum 41 and System of Down.

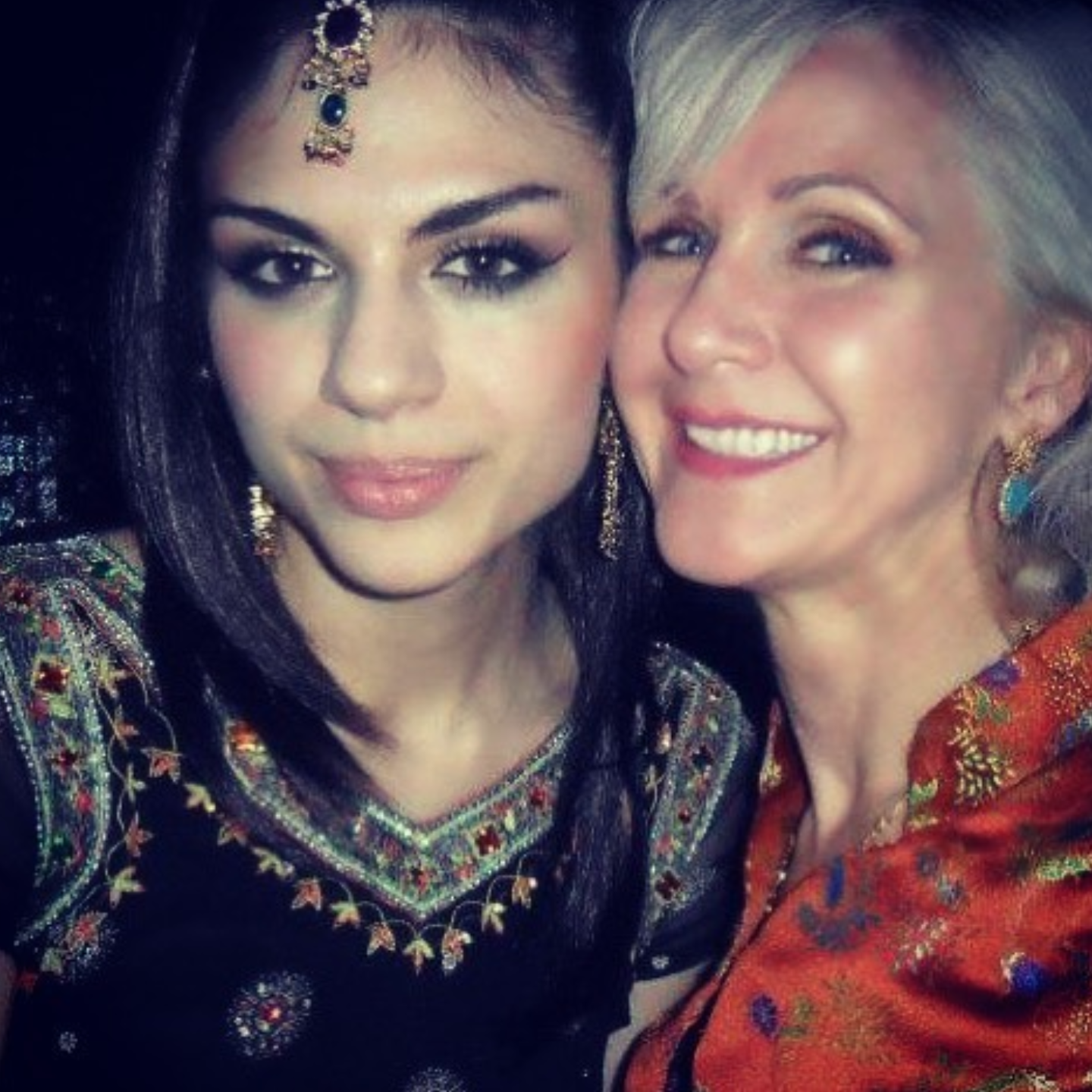

Krewella, the electronic dance music duo of Jahan Yousaf (l) and Yasmine Yousaf (r).

“There’s no right or wrong way to be an artist. I hope I continue to develop the courage to put my flawed, raw, rugged-self out there, so others can be inspired to release their own inhibitions or fears around being ‘imperfect.’”

ZA: Describe your creative process and how it has evolved during the last few years.

JY: Throughout the years, we have found that we can't create rules around how we create. Sometimes, inspiration happens through just being in the room with Yasmine and hearing chords she's playing or hearing a hook or a verse she's written.

For Yasmine and I, it's also blessing being sisters because we're both so committed to understanding each other more, growing together, embracing creative disagreements and seeing the beauty in them. That's really when the music magic happens.

New ideas can happen while on the plane, in the shower, in the car, climbing a mountain, traveling, or going to museums. We’re also really moved by visual art. I was so inspired on my last trip to Pakistan, taking in Mughal-era art, and absorbing many layers of ancient civilization.

Watch Krewella at work in the studio.

“Anything that allows emotions to flow, makes me feel connected with the world around me and connected to my ancestry just lights me up.”

ZA: That really illustrates how creativity can come from anywhere, that it’s accessible and need not be “earned” through pedigree or exposure from an advanced degree.

JY: Yeah, that’s true. I'm not classically trained and I've been working in music for 12 years. I just started learning guitar a few weeks ago. At any age, you can pick up a skill and tap into something that's a new interest — or maybe it's an interest from a previous life, something that you played around with as a kid, but has been dormant and waiting to be activated. Nurturing those long-lost passions and interests is the fountain of youth, in a way.

With all respect and admiration for well studied, technically trained artists and classical musicians, I think there is an instinctual, innate ability to create, imagine, and execute ideas in all of us. There’s no right or wrong way to be an artist. I hope I continue to develop the courage to put my flawed, raw, rugged-self out there, so others can be inspired to release their own inhibitions or fears around being “imperfect.”

ZA: What’s it like being two Pakistani-American women in the dance music industry?

JY: In the beginning of our career, we were welcomed with open arms by many people. And a lot of those fans—more than 50% of them—were men. To me, that was really exciting because growing up in the nineties and in the early 2000’s, I never, ever, ever thought it would have been possible to be up on stage as a woman, as a female storyteller. And to know that our perspective, our lyrics and our voices could resonate with men, I didn't think that was possible. In a way that shows our culture’s transformation and open-mindedness.

At the same time, there are still so many stigmas and barriers for minorities in the dance space- which is still predominantly white and male. There are forces within the dance music scene that continue to diminish and doubt the creative value that women and other minorities bring to the table. The truth is, the heartbeat of dance music is deep-rooted in the way minorities, people of color, and LGTBQ communities transmuted their rejection and suffering into a cathartic, euphoric outlet for all.

We have a long way to go with gender equity in the music industry in general, but we’re also having conversations that didn't happen in a mainstream way 10 years ago, embracing and validating the plethora of female and minority talent that exists in the dance space.

“I think fans are becoming more curious, and are looking beyond the headliners and what is spoon-fed by the mainstream to seek incredible, diverse, talent in the underground. ”

ZA: You make a good point on fans wanting more diverse talent that is more honest about identity. How do you see your own identity evolving over the years?

JY: I've struggled when I'm speaking about being raised Muslim or when people asked me if I am a Muslim. Those moments compelled me to ask myself what it means for me to be a Muslim. Islam was so integral to my experience growing up, and, in hindsight, I realize I didn't appreciate it growing up. When you're a mixed kid growing up in the States, you just want to be like everyone else.

But I think my relationship to Islam has changed as I’ve matured. In my own way, I've taken pieces of what I recall and integrated it with my own ideas around spirituality. This has changed my view of religion in general, and I appreciate the that its and intimate and personal experience for everyone. As I get older, I also feel my Muslim upbringing exists as a thread that connects me to my childhood. So, in a way, religion is also nostalgic for me, as I re-visit what I grew up around with new eyes and a deeper sense of appreciation and curiosity.

ZA: What were your impressions of Pakistan as a child?

JY: My first trip to Pakistan was when I was four years old. I have only fragments of memories, like going into a kusa shop and attending the wedding of a family member. Other than that, my exposure to Pakistan was formed from the stories, traditions, clothing, mannerisms, and mindset that my relatives carried with them to the United States. In Chicago, my parents would take us to Devon Street, an enclave of Indian and Pakistani businesses and restaurants. Each Sunday after Islamic school, our parents would take us there for desi food. It felt like a little slice of Pakistan within the midwest.

Krewella traveled to Pakistan in 2018 to perform on Coke Studio.

ZA: You’ve launched a wellness clinic in an underserved part of Pakistan. Can you share the genesis of this project?

JY: I had felt a desire for some time to do something in Pakistan that empowered those in need, but I didn’t have an outlet for it. At the beginning of 2020, I set a goal to visit Pakistan that year. The calling felt like it came from the depths of my soul, and I wanted to do everything in my power to make the trip happen that year. And then, the world shut down because of COVID-19. We postponed the trip. Amidst the lockdown and with plenty of down time, I started doing research on how I could give back to Pakistan.

I learned that a friend of our family had set up a nonprofit school in Nagar, a very small village deep in the mountains of northern Pakistan where little government support reaches and minimal infrastructure exists. The school provided much needed education to the children but also provided food donations to the impoverished villagers.

I started brainstorming with my father's cousins, Samira and Noshi, about how we could contribute to this village with a project of our own. We started thinking about causes that are really close to heart. What resonated with all of us was the goal of bringing free health services to women and children in this village - a desperately needed service.

As we did more research, we learned of really tragic stories of women dying on the side of the road during childbirth because they couldn't make it to a medical facility in time. we learned about the challenges of menstrual hygiene, such as not having proper bathrooms or menstrual pads.

Access to good healthcare is something we related to and felt very strongly about, especially because it has been monumental to our own well-being and healing. We know how life-changing such services can be, so we set out to help fix the weak state of health for women in this village. we believe that overall wellbeing and good health is directly related to the ability of women to thrive economically, continue their education, and help support their families.

After extensive research and consultation with the local community, we finally launched Nagar Women’s Health House in February 2021 which serves Nagar and nearby villages every day by offering free medicine and medical services.

Jahan visiting Nagar Women’s Health House in Pakistan

“I believe that overall wellbeing and good health is directly related to the ability of women to thrive economically, continue their education, and help support their families.”

Yousaf with the local staff of Nagar Women's Health House.

ZA: It takes a lot of planning to launch an initiative like this. What are you envisioning for the next few years?

JY: When we started, we had a huge vision of a clinic that provided free services but that would also serve as a community center where women could get together regularly and have nurse-guided conversations about their health. We were really excited and had many ideas, but recognized that we had to start with achievable goals and focus on the absolute essentials, such as procuring the ultrasound machine, supplying medicine, and hiring nurses and a doctor.

We’ve now checked off those basic goals we had, including having hired an all-woman staff and a gynecologist. We have done this all under the guidance of the legendary Dr. Meher Akhtar, a leader who has a lifetime of experience volunteering her time to impoverished communities in Pakistan to bring them health services.

A health class for children at Nagar Women’s Health House.

We are now focusing on how we can go beyond just giving free medicine and services to empower the community to sustain the work we’ve started. We believe this can start by creating an environment where the women who are business owners, students, entrepreneurs, or health leaders can take the vital knowledge they receive from the clinic and disseminate it to their communities.

ZA: Could you share any reflections for those of us who want to give back to Pakistan but don’t know what first steps to take?

JY: Volunteering and community service is a direct way to get in touch with your community. With the help of the internet, there are infinite ways to give back, get involved, fundraise, and share information about social causes. My advice would be to keep searching for opportunities and stay curious because there are so many grassroots projects and local community-based organizations with an online presence. If you want to give back, pay attention to what work aligns with your values and who shares the same heartbeat as you.

Even though Nagar Women’s Health House project is based far away in the mountains of Pakistan, we continue to feel close to it because our local coordinator Ghazi sends us daily reports, photographs, and videos of the clinic’s work.

Yousaf in Pakistan with her father

That's how our whole team, despite being isolated from each other in the pandemic, was able to connect over a common cause. With family members and friends based in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Pakistan, we formed a digital team that led to the establishment of a much-needed clinic for the people of Nagar - and we are now connected to that community for years to come. And technology allows us to keep those connections strong.